This report is a presentation of our analysis of the Google Chrome web browser, which was developed as part of the Chromium open-source project1. Our mission was to develop a conceptual architecture of Google Chrome using the existing documentation. Through this research, we came to a predominantly Object Oriented architecture. We will go into further detail regarding the architecture style and the subsystems present, as well as how we arrived at this model. We will explore the functionality of our architecture through two sequence diagrams, depicting different use cases. Finally, we will conclude with team issues and lessons learned. This report will act as a foundation when developing a particular architecture in the future.

Google Chrome is an internet browser written using C++2. The stable branch offers significant updates every six weeks, and minor updates every two or three weeks3. However, users have the option to get faster update cycles on less stable branches3. The Chrome project focuses on four main non-functional requirements: simplicity, speed, security, and stability4.

To better understand Chrome, we first defined who the stakeholders of Chrome were, and their interaction with the software. The most relevant stakeholders are outlined below:

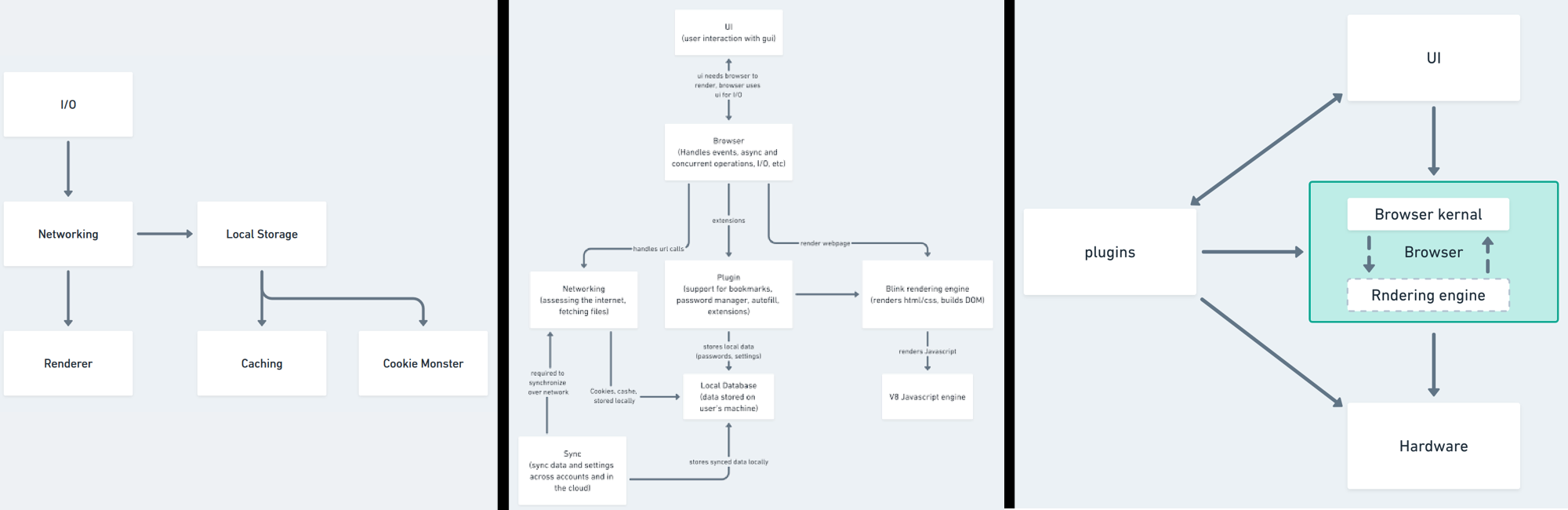

Our group tackled this challenge by first splitting up into three groups of two. We individually researched the architecture of Chrome (using many of the resources found during Assignment 06), and each created a model of what we determined the architecture to be. We then met up and were quickly able to identify the disagreements we had between our architectures. Through further research and constructive debate, we formed a synthesis of our initial concepts that we could all agree upon. Research into each component allowed us to refine this final version better and justify our decisions. Pictured below are three of the first architectures that we developed.

As you can see, some of our architectures differed in scope (Diagram C was too broad), differed in naming (Diagram A uses names that were different from those others came up with), and some contained subsystems we determined were unnecessary (such as with Diagram B). Through this process, we concluded on a Network, Browser, UI, and Local Storage component, and moved V8 into its own subsystem, as it better represented the documentation we found.

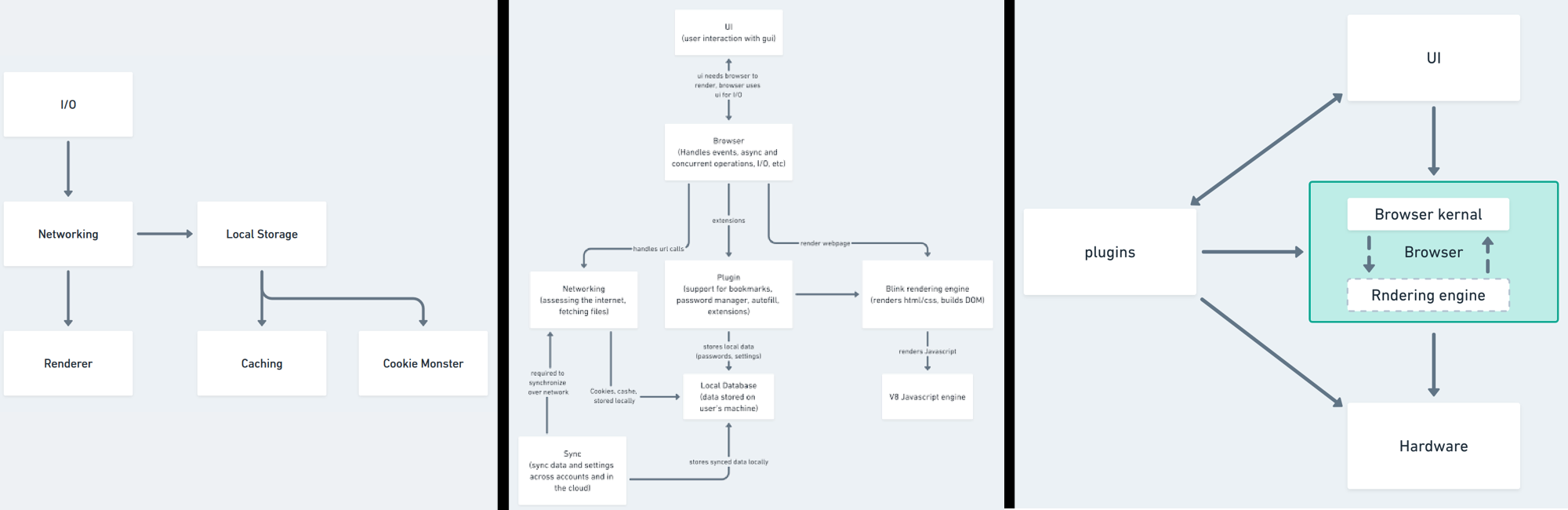

Our architecture mainly uses an Object Oriented architecture style, which enables each subsystem to be developed, more or less, discreetly from the rest of the system. This allows the Chromium team to develop the UI separately from the Network subsystem (for example), and is one of the reasons Chrome can have a short development cycle. The benefit of this architecture is that it has high cohesion and low coupling, both of which allow the software to be developed and maintained more easily.

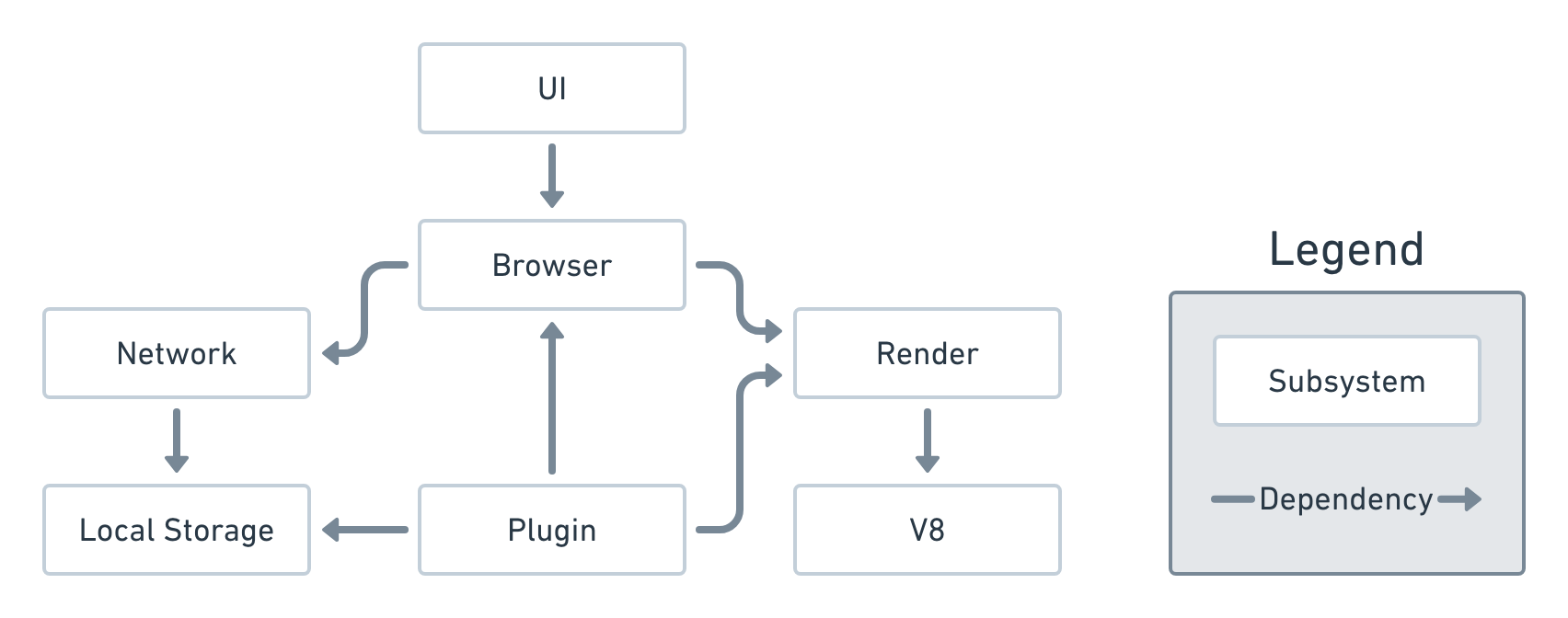

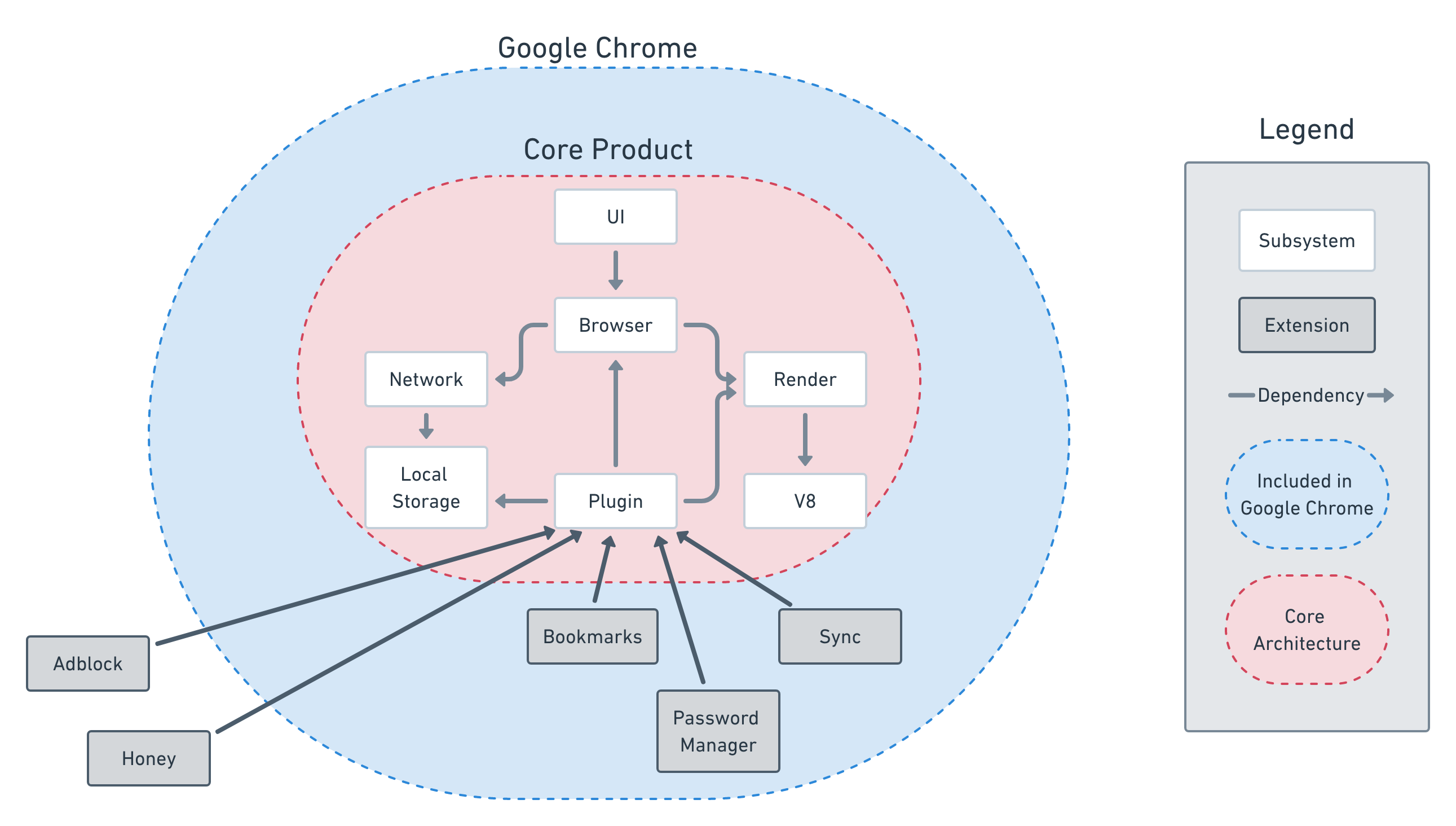

Although the conceptual architecture we will discuss in this report is Object Oriented, when the components are rearranged, a Loosely Layered architecture is revealed (Fig 3). It is not strictly layered due to the Plugin subsystem's ability to access the Render and Local Storage subsystem directly, however, we decided that it would not be practical for Plugin to make these requests through Browser (further explained in the Plugin section). Because of these inconsistencies, we decided that the Object Oriented diagram (Fig 2) represented our architecture model better. Despite this, we still feel that the Layered diagram is useful for understanding aspects of how our architecture functions. For example, it clearly shows the two highest layers of the system: UI (the central subsystem the user interacts with), and Plugin (the subsystem 3rd-party developers interact with).

The Local Storage subsystem is the component in charge of storing data onto the user's computer. As multiple subsystems require the ability to save data to the user's machine, it becomes necessary to create a subsystem to outsource this work. This increases cohesion within those subsystems and reduces the amount of code that needs to be rewritten. Local Storage should also be capable of encrypting and decrypting files, allowing for the safe storage of passwords and other sensitive data. As a further security precaution, Local Storage should limit the access components have to the data stored. For example, preventing the 3rd-party extension from accessing data saved by the Password Manager7. Local Storage does not depend on any other subsystem; it is its own discrete system.

The Network subsystem, or "Network Stack" as it is referred to by the Chromium team8, is the subsystem dedicated to fetching and returning requested files. It is passed a URL, which locates the desired resource. Network fetches this resource and returns the file to the Browser subsystem9. Network is also used to retrieve the cookies, host resolver, and proxy resolver that is associated with the inputted URL (this "context," however, is returned through a separate request from the previously described URL fetch9). We believe that the Network subsystem would also be capable of following file paths on the user's computer, such as when you open a PDF in Chrome, and it displays the file under a URL like "file:///Users/usr1/filename.pdf". This capability would allow the Browser subsystem to request any resource from Network (regardless of type); although we were unable to find any documentation that confirms or denies this.

Network only depends on the Local Storage subsystem. This subsystem is required for saving long-term data (such as cookies, cached files, etc.) on the user's machine.

Despite most operating systems having their own command or framework for accessing the internet (such as wget, or curl), the Chromium team chose to develop their own cross-platform framework for doing these operations within Network8. Their decision to create their own system was made to eliminate bugs found in the native frameworks and allows them to build faster and more efficient processes for retrieving content8. As "speed" is one of the product's four main non-functional requirements4, the investment into the development of such a system was worth it to the Chromium team.

The Browser subsystem is the central backend subsystem of our architecture. It is not to be confused with "the browser" in the general sense (which is often used to mean the concept of a web browser), but rather the subsystem that the Chromium team refers to as the "Browser Kernel"10. It handles events, and delegates tasks to the subsystems layered underneath it. Chrome's concurrency model requires a dedicated subsystem to create and manage new instances10, and the Browser allows one centralised unit to do so. The Browser has four primary responsibilities:

The Browser depends on two subsystems: Network and Render. Network is required for fetching resources such as web pages, which the Browser then renders. To render these web pages, the Browser depends on Render11.

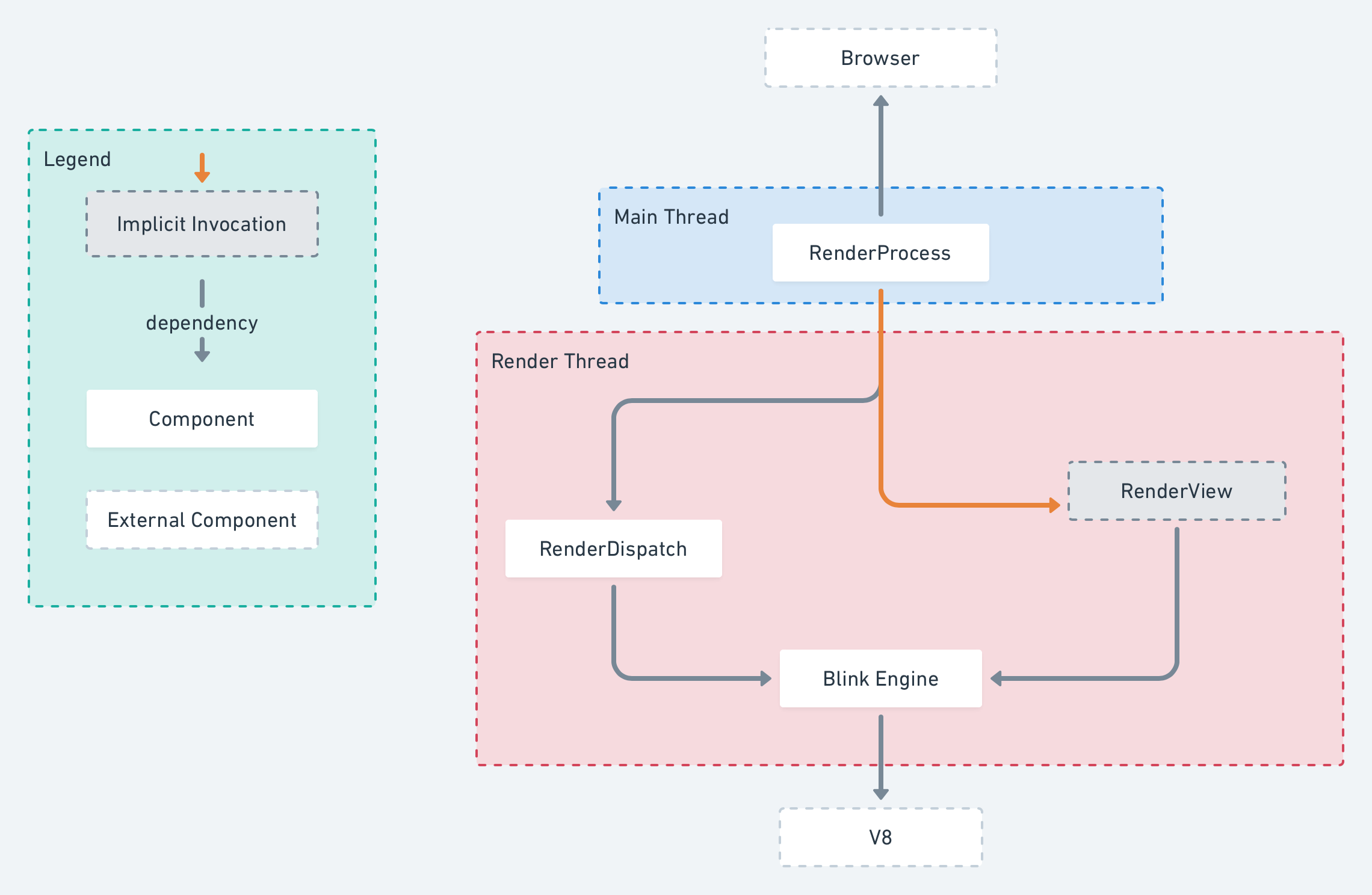

The Render subsystem is the primary subsystem that handles the code painting and rendering for the browser. The way Render works, is for each render process request from Browser, the renderer spawns a new RenderProcess in the main worker thread. This handles all communication to the Render thread that performs a majority of the heavy processing12. Within the Render Thread, there is a Render View Controller. It can be implicitly invocated depending on the required amount of Render Views needed to maintain site isolation. Also contained within the Render Worker Thread is the Resource Dispatcher. This is responsible for dispatching all resources13 that Blink requires to complete the actual rendering of the elements. Finally, Blink is the main rendering Engine for the Render Process. It does all the heavy lifting, such as running animations, building the DOM, passing and rendering HTML/CSS, and handling memory. Blink spawns a new V8 worker thread, and the JavaScript on the page is compiled and ran using the V8 APIS11. Blink is the subsystem required to send V8 the DOM, as V8 is unable to build this itself.

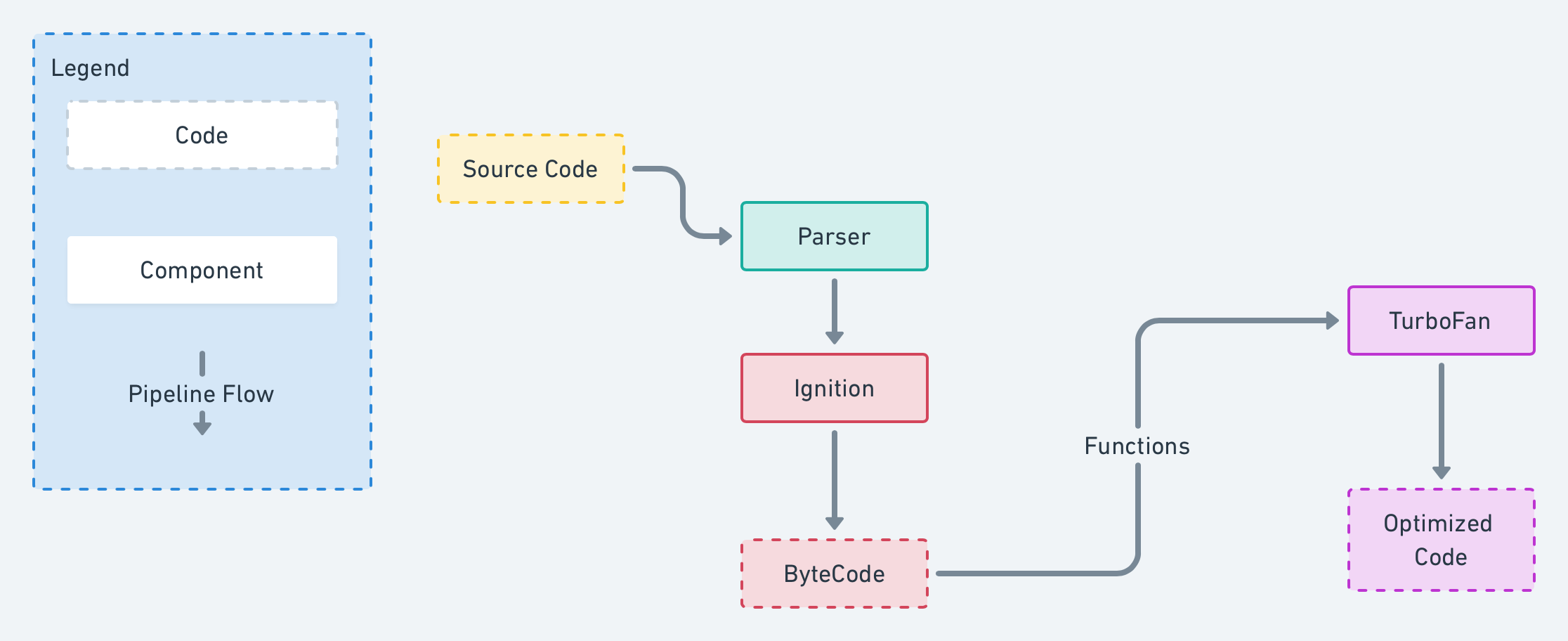

V8 is the subsystem responsible for interpreting/compiling javascript and running it on the hardware. V8 uses an interpreter and compilation pipeline for efficiency. In this process, the code is interpreted by Ignition into bytecode; however, functions are left as references at this stage. Functions are instead passed to Turbofan and compiled for faster execution14. V8 also uses a Generational Garbage Collector, as V8 handles memory allocation. Every time there needs to be me more memory allocated to an object, V8 checks if they have existed for 5 different allocations, in which case they are labelled "old" and freed from the heap15. Once the JavaScript has run, anything that needs to be rendered is passed back to the Blink engine.

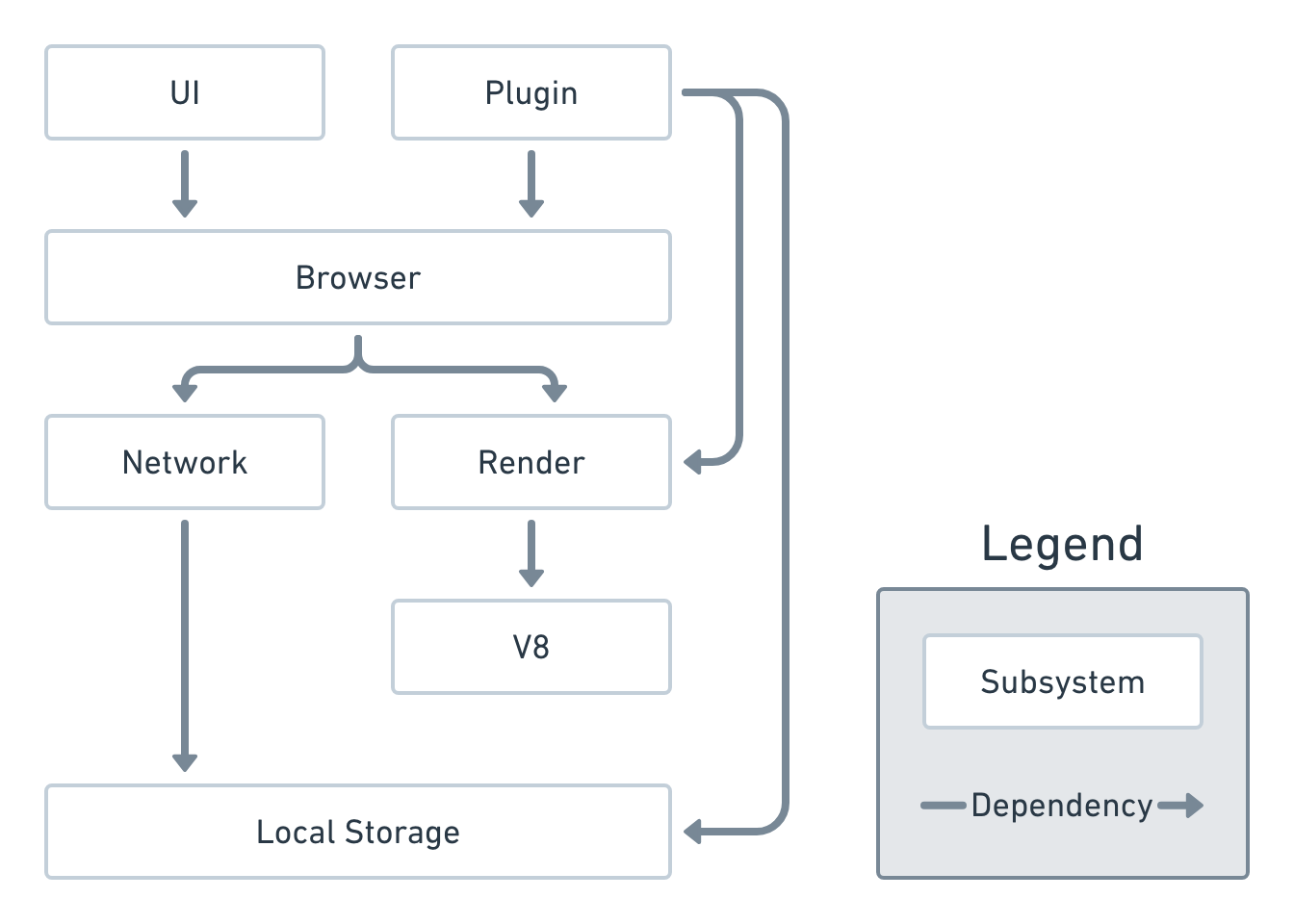

The Plugin subsystem is the subsystem in which Chrome Extensions are built on top of16. These extensions are not developed as systems inside of the plugin component, but rather, extensions are built using the plugin component. By doing so, Chrome can limit extensions to one entry point in the architecture (Fig. 6). The Plugin subsystem is sandboxed by Chrome16, limiting privileges and resources to extensions.

Chrome Extensions are built using this subsystem5. These extensions range from content blockers such as Adblock17 to coupon-finders like Honey18. The Chromium team also builds additional features of Chrome using this same subsystem. These features include all non-essential additions to the application, such as Sync19, Bookmarks, and even the Password Manager. Despite these features being included in Chrome by default (unlike 3rd-party extensions), it makes sense to build them with the Plugin subsystem as it prevents anyone subsystem becoming bloated with these new features and lowers coupling. Instead, each new feature can be written separately from the rest of the software, allowing for the Chromium team to update the UI without making changes to the Sync extension, and to develop the Password Manager without affecting the rendering engine (for example). A diagram explaining this idea is depicted below.

The Plugin subsystem has three dependencies: Render, Browser, and Local Storage. The system requires Render to interact with the DOM tree directly. By reading and editing the DOM tree, extensions can inject themselves into the webpage (such as Adblock removing advertising elements from the page). Local Storage is used to save data to the user's computer, such as settings7, passwords, etc. However, each extension only has access to the files it creates, preventing malicious 3rd-party extensions from accessing sensitive user data. Finally, the Plugin subsystem depends on the Browser subsystem to provide it events (new webpage, I/O event, etc.), and to make network requests. The Plugin subsystem does not have direct access to the Network, and therefore must go through the Browser to request these resources. This allows the Browser to vet the extension's requests.

The UI (User Interface) component is the subsystem allowing user interaction with Chrome. By creating a discrete subsystem to handle the user input, the Chromium team can update the design of Chrome frequently, without affecting the functionality of the software. The UI subsystem depends on the Browser subsystem to supply it with the webpage, extensions, URLs, and any other information the UI will need to render the application window. Note that the Render subsystem and V8 have already processed the webpage; the UI must instead render the webpage in the application window and display it to the user.

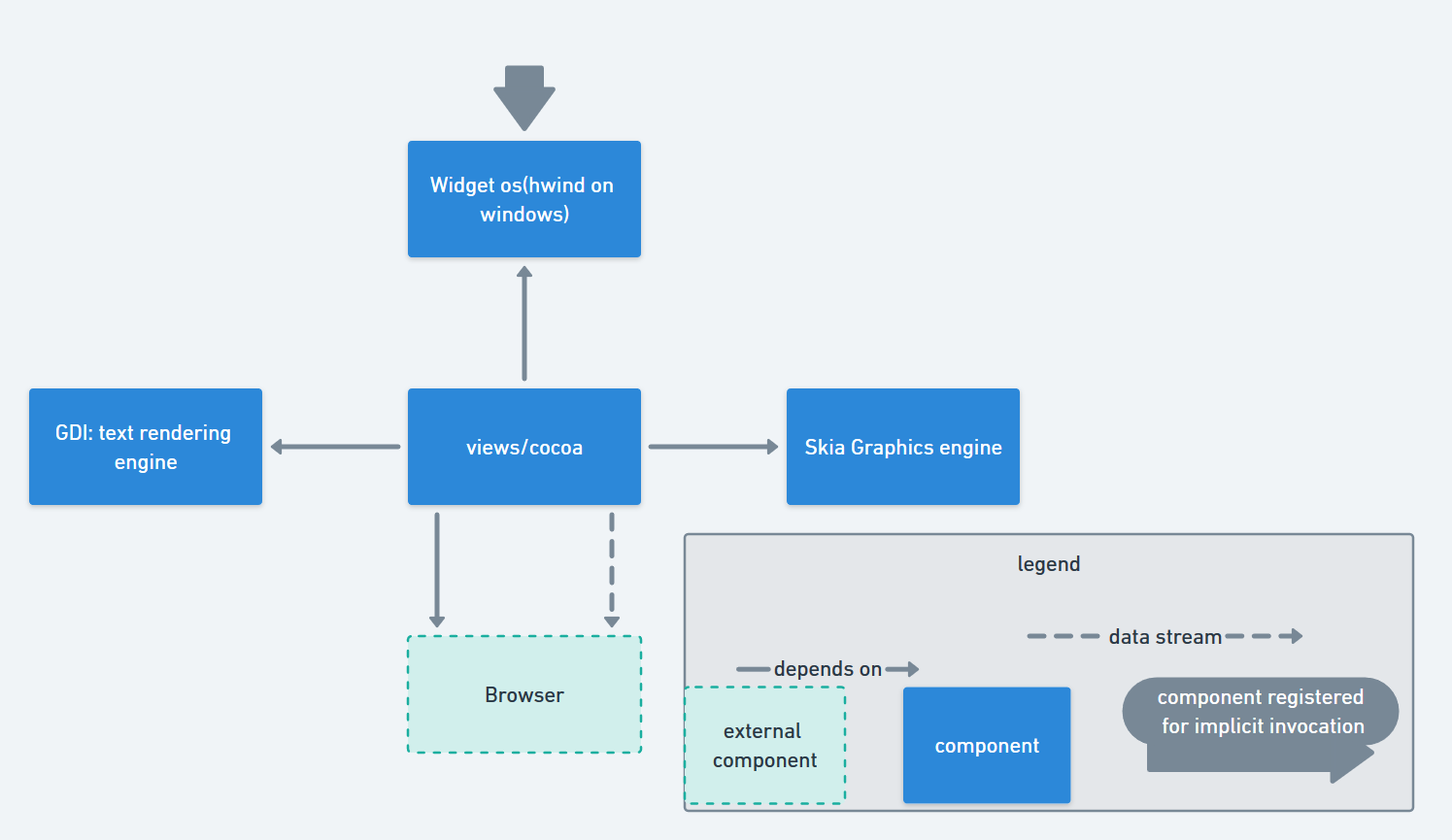

One of the two subsystems we chose to investigate is UI. Our architecture is a combination of Objects and Implicit Invocation.

The Views subsystem is a cross-platform component responsible for layout, UI rendering, and event handling20. Views are used on Windows, Linux, and Chrome OS, however, the native UI framework is used on MacOS, iOS, and Android21. The subsystem works by having layers of "views."

Views rely on three subsystems within UI: Skia, GDI, and Widget OS. Widget OS is used to render certain UI elements, such as such as text fields, tables and radio buttons, from the OS’s built-in features22. These elements could be rendered using GDI and Skia, however doing so would be inefficient, as the OS does these natively, and the subsystem could not be cross-platform (each OS would differ). Widget OS also is registered with the operating system to receive messages (These messages include things like WM_PAINT and WM_LBUTTONDOWN23) from the OS. Views depend on Widget OS to translate these OS messages into an understandable format. The second of these systems is the Skia Graphics engine, which Views use to render non-text portions of the UI such as SVG, Canvas, etc22. Finally, the GDI subsystem is responsible for rendering text portions of the UI, such as fonts22.

Chrome has many different Concurrency Models. The main one is done through Javascript workers and a process called Site Isolation24. To reduce XSS points, Chrome uses a Process-Per-Site-Instance model where a new Render Process is created per individual object that needs to be rendered25. Chrome uses a communication standard named IPC; however, this is currently being replaced by a system called Mojo26. All data and the creation of a process is made concurrently using this system. Chrome also uses standard Javascript runtime concurrency for code execution; the heap, stack, queue model26.

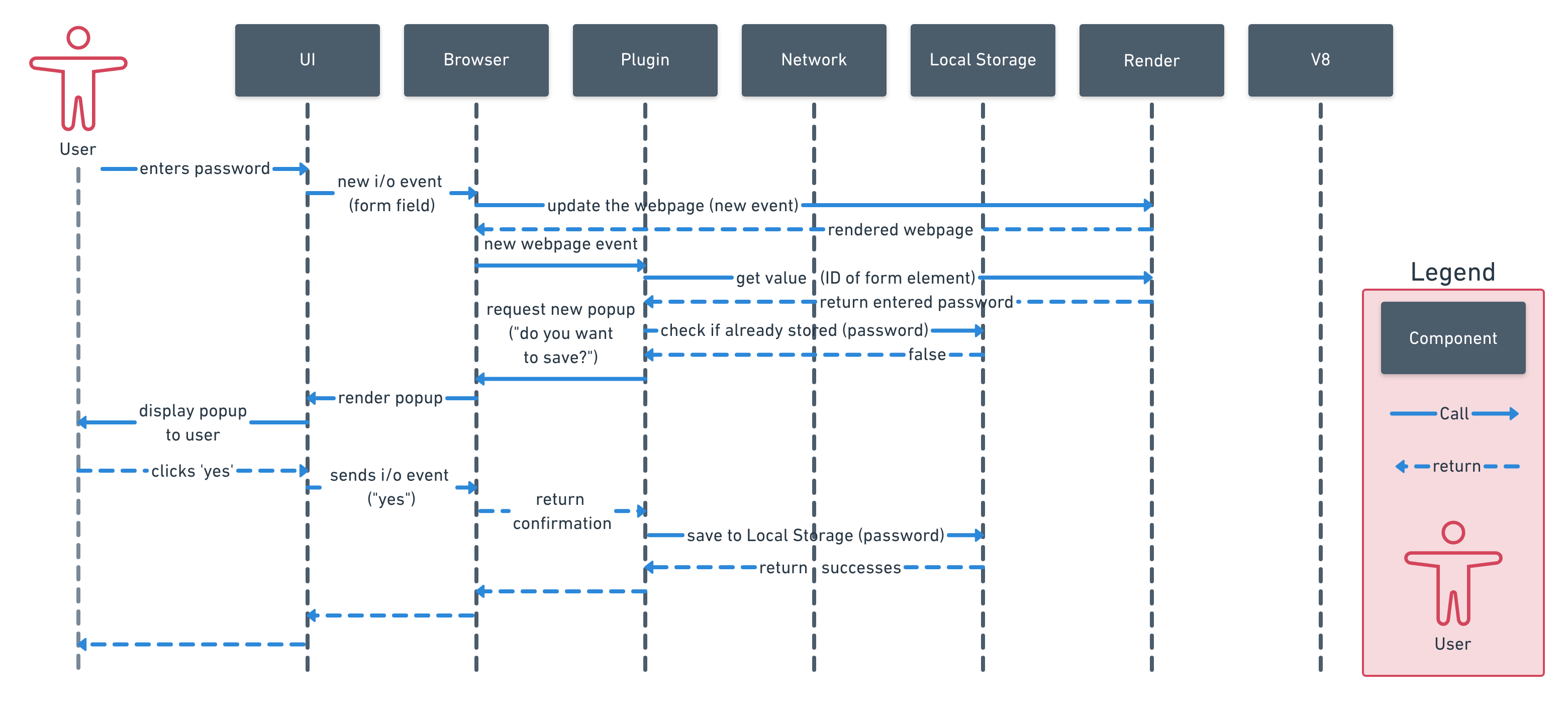

To explore the functionality of our conceptual architecture, we developed sequence diagrams depicting two use cases provided to us:

The sequence diagram starts with a user entering their password, prompting the UI to send a new I/O event. This is handled by the Browser, which then requests the Render component to update webpage. Once the webpage is updated, the Browser sends a new event to the Plugin component. The Password Manager (which is built using this Plugin component) is notified of this new event assesses the DOM tree generated by Render to view this inputted from data. Render returns the form's value (the password entered) to the Password Manager. The Password Manager checks Local Storage to see if the password entered has already been saved. In this use case, Local Storage returns that this password has not already been stored. The Plugin requests the Browser to create a new popup, which is then rendered by the UI, and finally displayed to the user. The user confirms that they would like this password to be saved by clicking "yes," triggering a new I/O event. The Browser notifies the Password Manager of this confirmation, and the Password Manager saves the password to the computer using the Local Storage subsystem. These steps are successful, as per the use case, and each subsystem returns "success".

This second sequence diagram shows Chrome rendering a webpage that contains JavaScript. The sequence begins with the user making a request to load a URL. The UI component takes this request and passes it to the Browser which then sends this URL request to the Networking component. The page content is then loaded and returned to the browser (not yet rendered). The render request is sent to the Render component which renders the web content that is not JavaScript (CSS, HTML etc). The JavaScript element(s) is passed over to the V8 Render Engine to be processed and passed back. With this rendered, the webpage is then passed back to the Browser, then to the UI, and finally displayed to the User.

In summary, our Google Chrome Architecture follows an Objected Oriented style as well being loosely layered. This is what allows Chrome to have such a quick development cycle as subsystems can be updated independently of each other. Furthermore, the sandboxing of the Plugin subsystem makes it easy for users to use 3rd-party extensions without sacrificing security. We also found that Chrome's ability to run all subsystems concurrently increases security, but can cause poor performance.

Moving forward, we will dig deeper into the available documentation and source code to construct a concrete architecture of Google Chrome. The understanding of Chrome we have developed also may be useful if we chose to extend the functionality of Chrome at some point, such as building our own Chrome extension. To determine what improvements should be made we will look to other popular browsers to see what they might be doing that Chrome currently lacks or determine why Chrome is more popular, and refine these aspects.

The most important thing we learned during this project was discovering how we worked most effectively. At first we tried to split up into pairs but we quickly found that most of our work was accomplished when we were able to sit down together. Moving forward we will make a greater effort to find times for the whole group to get together and tackle problems. The other big thing we learned was that it can be very helpful to use resources outside of Google's own documentation to gain a better high-level understanding of the architecture or subsystems. The Google documentation could provide a lot of detail but could often be difficult to comprehend. If we could have done something differently it would have been to start with using 3rd-party references to gain a general understanding then use the Chromium documentation to investigate specific areas.

https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/master/styleguide/styleguide.md ↩︎

https://www.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/network-stack ↩︎

https://www.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/network-stack ↩︎

https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/master/net/docs/life-of-a-url-request.md ↩︎

http://dev.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/multi-process-architecture ↩︎

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1aitSOucL0VHZa9Z2vbRJSyAIsAz24kX8LFByQ5xQnUg/ ↩︎

https://www.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/multi-process-architectureedit#heading=h.p8sox77u21on ↩︎

https://www.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/multi-process-resource-loading ↩︎

http://benediktmeurer.de/2016/11/25/v8-behind-the-scenes-november-edition/ ↩︎

https://medium.com/@_lrlna/garbage-collection-in-v8-an-illustrated-guide-d24a952ee3b8 ↩︎

https://www.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/plugin-architecture ↩︎

https://www.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/chromeviews ↩︎

https://www.quora.com/What-kind-of-UI-framework-is-Google-Chrome-using ↩︎

https://www.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/graphics-and-skia ↩︎

https://www.chromium.org/Home/chromium-security/site-isolation↩︎

https://www.chromium.org/developers/design-documents/process-modelsa>↩︎